Red River Settlement

|

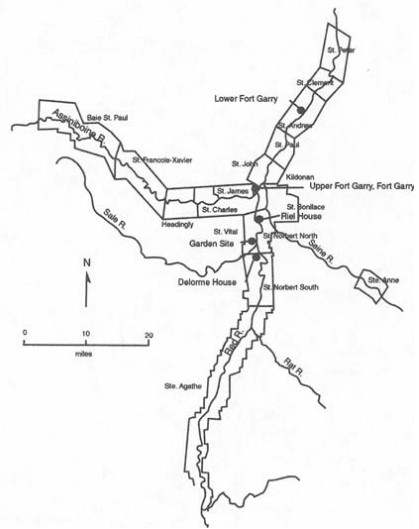

The Red River Settlement refers to permanently and semi-permanently inhabited areas along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. The Parishes of St. Boniface, St. James, St. Charles surrounded the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers where Upper Fort Garry was located; adjacent to these were the Parishes of St. John and St. Vital. From there, it extended north along the Red River through the Parishes of St. Paul and St. Andrews, past Lower Fort Garry to the Parishes of St. Clement and St. Peter. To the west along the Assiniboine River, it included the Parishes of Headingly, St. Francois-Xavier and Baie St. Paul. Along the Red River, it included the Parishes of St. Norbert and St. Agathe. The Parish of St. Anne along the Seine River to the east is also included. While Indigenous people had used the area around the Forks for millennia, the founding of the Red River Settlement dates to 1811. The first group of Lord Selkirk’s settlers arrived the following year. The area experienced a major increase in population (and decrease in tensions) after the amalgamation of the Hudson’s Bay and Northwest Companies in 1821. Upper Fort Garry, located at the centre of the Red River Settlement, was the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The HBC controlled the import, export and marketing of goods harvested from the land and those shipped in from Europe during the early years. Challenges by the Metís ended the HBC monopoly in 1849, allowing goods to be shipped in from St. Paul. By the 1860s, paddlewheel steamboats from the United States had largely replaced Red River cart brigades.

|

Map of the Red River Settlement (from Brenner and Monks 2002) |

After 1821, many retired fur trade company employees settled in the area according to their ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. English-speaking Presbyterian and Anglican settlers of Scottish, English, Irish descent, including Orkneymen and Countryborn, resided north of the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. French-speaking Roman Catholics of French and Metís heritage settled to the south. Hudson’s Bay Company employees and retirees, such as James Bird and Cuthbert Grant, were among the wealthiest individuals in the Red River Settlement.

Until 1870, permanent houses were usually constructed from squared oak logs using mortise and tenon (tongue and groove) techniques. Upright logs with vertical grooves extending their length were placed at the four corners of the structure, at doorways and periodically along the walls. Each upright had a tenon post cut into the base to form a joint with a horizontal sill. Horizontal logs with tenon tongues on both ends were then slid into place between the grooved uprights to form the walls. These Hudson’s Bay or Red River houses were often built on a stone foundation and had thatched roofs. By the late 1840s, wood became scarce and logs had to be harvested long distances away then floated in booms to the construction site.

The Metís of the Red River Settlement were divided into three socio-economic groups: Tripmen, Hunter and Farmer-Merchant. Most Metís were either Tripmen or Hunters, many of whom spoke Michif. Until the late 1860s, they took part in the semi-annual bison hunts then spent the fall and winter at the Red River Settlement on available river lots. Without legal claim, many moved west in the 1870s after the Dominion government expropriated their land. The smallest and wealthiest Metis group consisted of Farmer-Merchants.

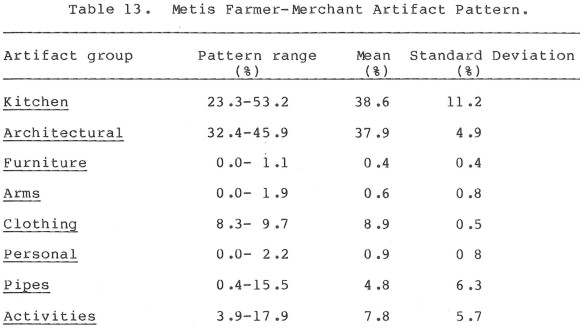

| Archaeological excavations were conducted at the locations of three Farmer-Merchants in the 1980s: Delorme House, Riel House and Garden House.Based on his analysis of the excavated material, Mr. K. David McLeod proposed the Metís Farmer-Artifact Pattern. He suggested that artifacts categorized as “kitchen” or “architectural” formed upwards of 76% of the assemblage, on average. Much of the remainder consisted of artifacts related to “clothing” (8.9%), “activities” (7.8%) and “pipes” (4.8%). All other categories of artifacts made up only 2% of the total assemblage. |

From McLeod (1985) |

Brenner and Monk Brenner and Monk compared ten artifact assemblages from the Red River Settlement sites to information gleaned from archival documents, such as census, employment and military records. The residential /domestic assemblages could be associated with specific families; assemblages from Upper and Lower Fort Garry areas could be associated with discrete individuals or groups within forts. Brenner and Monk found that the characteristics of ceramics found in the artifact assemblages accurately reflected variation in wealth, measured by wages, occupation, and possessions, of the people associated with them. More costly ceramic assemblages generally reflected higher social position. Anglophones were more likely to have Copeland/Spode ceramics, which were imported from England by the HBC; after the HBC monopoly ended, Francophones purchased American ceramics in quantity.

References:

Brenner, Bonnie Lee A. and Gregory G. Monks

2002 Detecting Economic Variability in the Red River Settlement. Historical Archaeology 36 (2): 18-49.

Brown, Jennifer S. H.

2006 Michif. The Canadian Encyclopedia (online). Updated by Michele Filice. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/michif. Accessed March 2021.

McLeod, K. D.

1985 A Study of Metis Ethnicity in the Red River Settlement: Quantification and Pattern Recognition in Red River Archaeology. M. A. thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

Wade, Jill

1963 Red River Architecture, 1812-1870. M. A. thesis, Department of Fine Arts, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.